Orchids, forests, landscapes, and the visionaries who designed them: these are a few things that inspire me. On a recent trip to the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, I photographed orchids in the Biltmore Conservatory, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted. While there, I was reminded about a trip to Key West in 2009, where we stayed at The Gardens Hotel, which had a beautiful garden designed in the 1930s by another visionary gardener.

Join me on a ramble through some famous historical gardens…

Table of Contents

The Gardens Hotel: A 1930s Garden by Our Lady of the Orchids

Caring for the Orchids at The Gardens

The Biltmore Estate Gardens and Conservatory

Some of Frederick Law Olmstead’s Projects before Biltmore

The Beginning: Olmsted’s Vision

Dr. Carl Schenck & The Biltmore Forest School

Pisgah National Forest & the Cradle of American Forestry

Orchids, forests, landscapes, and the visionaries who designed them…?

Video: Orchids at the Biltmore Conservatory

The Gardens Hotel:

A 1930s Garden by Our Lady of the Orchids

In 2009, Michael and I spent a week in Key West at The Gardens Hotel. (It was heavenly.) Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the property features an incredible garden built from scratch in the 1930s by a woman named Peggy Mills, who had a vision of turning the (then barren) property around the home into a botanical garden for the public to enjoy. She became known as “Our Lady of the Orchids,” because she collected so many rare orchids from Japan and Hawaii and planted them everywhere in her garden so that everyone could enjoy their beauty.

In her garden, orchids hang from tree branches and grow on the sides of trees and in the nooks of branches. Orchids grow in pots, large and small, and hang from planters from the branches of trees. Each day, a few times a day, I strolled through that garden on paths paved with antique bricks from Cuba, Honduras, and England, finding something to amaze me at every turn.

Caring for the Orchids in The Gardens

I learned something from that visit changed the way I feed and water my own orchids, and I think is one reason I am able to keep orchids alive and reblooming for years.

I noticed that when a hanging orchid needed feeding or watering, they would take it down and plop it into a bucket of water or water with a bit of fertilizer and allow it to soak for an hour or so and then hang it back up to drain. I asked about it, and found out that this method of soak and drain, if you can do it, is healthier for the roots of the plants than watering them from the top.

As a result, I frequently do this at home. Once every week or so, I fill my outdoor kitchen sink with water and pop them all in to take a bath while I go do my chores. If they need fertilizer, I mix a little into the water. After an hour or so, I drain the sink and put them back into their catchpots. If their leaves are dusty, I swab them gently with a soft cloth while they are soaking. I have five older orchids around the house now that are budding up and getting ready to do their thing for spring (and I’m so excited!)

I have a huge appreciation for anyone with the vision and determination to take on designing a garden from scratch. At The Gardens, Peggy Mills bought and demolished 13 properties around hers to amass a quarter of a city block which she built into a breathtaking, quiet retreat for all to enjoy. I highly recommend it as a destination…I would love to go back.

The Biltmore Estate Gardens and Conservatory

Which brings me to the grounds and gardens of The Biltmore Estate, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, who in my estimation, was the greatest visionary landscape architect ever.

Not only did Olmsted design the grounds and gardens of Bilmore, he helped to birth forestry in the United States. It’s a cool story…

Some of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Projects before Biltmore

Frederick Law Olmsted didn’t begin work as a landscape architect until he was in his 40s when he was tapped by Calvert Vaux to help with a design for New York’s Central Park. Their design won, and Olmsted began an incredible career, culminating with his work at Biltmore.

- Central Park in NYC (1857)

- Jackson Park in Chicago (1871) which was remodeled in 1893 to be used as the site of the World’s Columbian Exhibition

- The US Capitol Grounds (1874)

- The Emerald Necklace (1878-1896) a 7-mile long chain of parks, waterways, and parkways in Boston

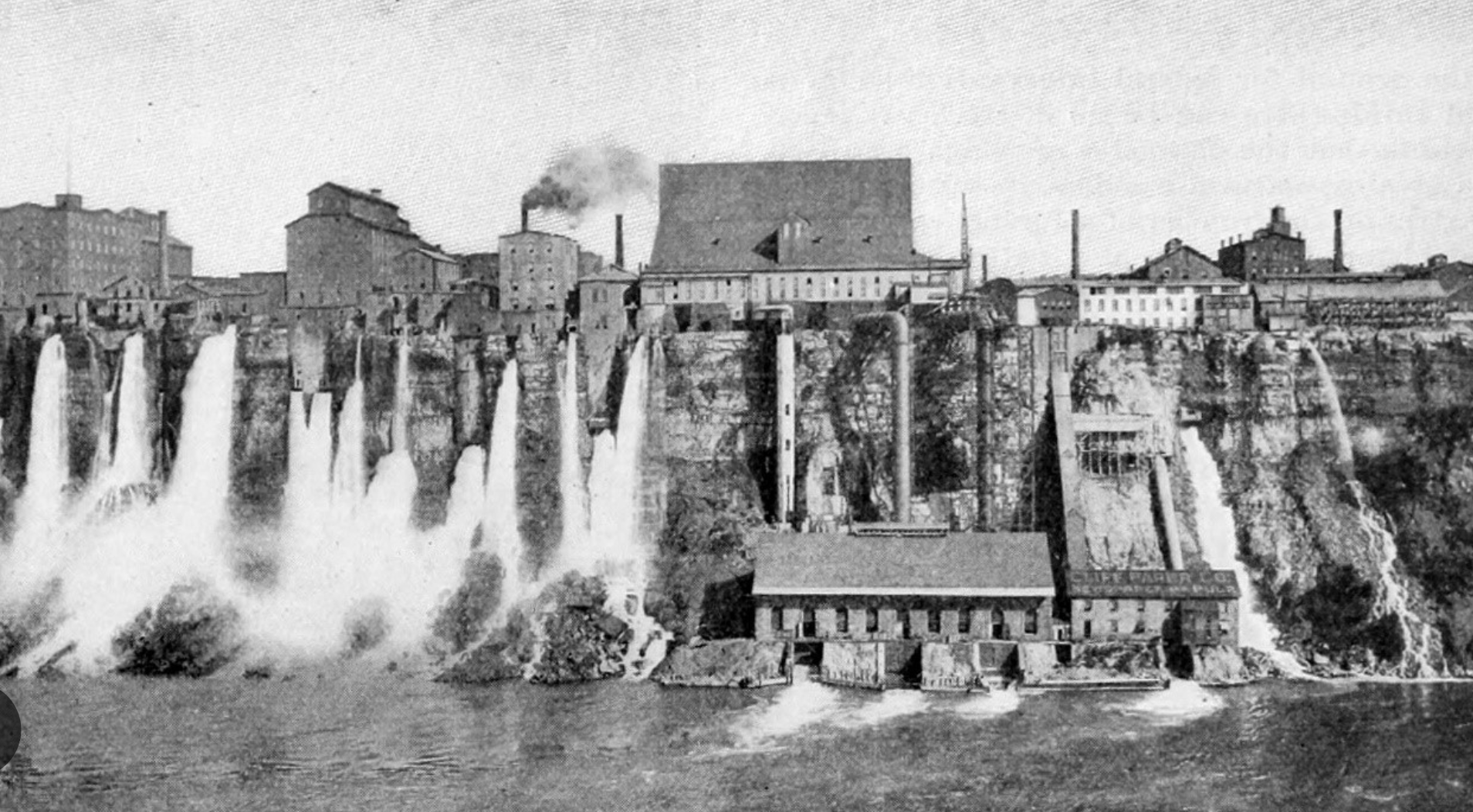

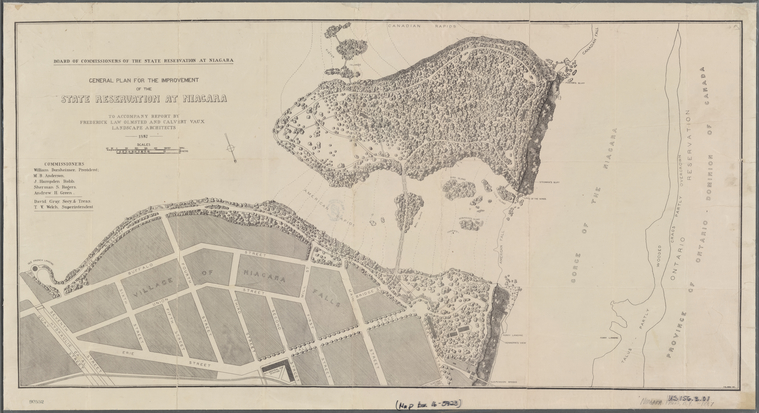

- Niagara Falls State Park (1885), after he and other environmentalists successfully lobbied the State of New York to claim back the land around Niagara Gorge to establish the first state park in the US. (Pictured top right is the river before it was freed.)

Jackson Park today

Summerhouse designed by Olmsted, US Capitol Grounds

The Niagara Gorge in the 19th century, “afflicted,” as Frederick Law Olmsted observed, by “mills and factories everywhere, hovels, fences and patent medicine signs.”

Plan for Niagra Falls Reservation

Jackson Park redesigned for the 1893 World’s Fair. Olmsted was working on this project at the same time he worked on Biltmore.

This c. 1892 image from Biltmore is entitled “Poor Woodland”

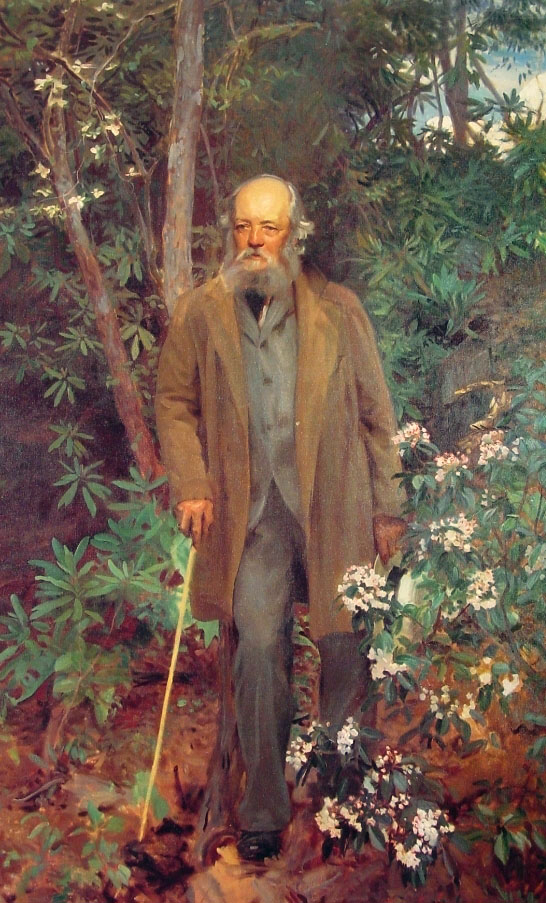

Painting of Frederick Law Olmsted by John Singer Sargent was commissioned by George Vanderbilt in 1895. It hangs at the Biltmore Estate.

The Approach Road leading up to the Biltmore Mansion as it looks today.

The Beginning

In the late 1880s, when George Vanderbilt began amassing his 125,000 acres of land in Asheville, NC, much of it was deforested and over-farmed. The woodlands had been overworked and were thick with undergrowth.

On his initial visit to the property when Vanderbilt asked him to come to the property to assess the first few thousand acres he had purchased, Olmsted described the homesite as “mostly deforested, flat, and scraggly,” and wrote in a letter that, “I was at my first visit greatly disappointed with its apparent barrenness and the miserable character of its woods.”

Biltmore would be Olmsted’s final project, some say his crowning jewel. As with all his other projects, his vision and design were born from the contours of the land and its vistas, its streams, and the beautiful French Broad River, which flows through the property. He designed the grounds with its the winding roads, paths, bridges, and plantings to provide people with gorgeous views of the natural environment at every turn.

Visiting Biltmore today, it is incredible to imagine the landscape Olmsted described seeing now that over a hundred years of growth are on his original design and plantings. Like all of his other endeavors, it is simply breathtaking.

Arial view of the Biltmore Mansion, the Conservatory, and forests as they look 120 years after Olmsted’s design.

Olmsted’s Vision

Olmsted’s vision for Biltmore extended far beyond the grounds around the house and the areas leading up to it. By 1895, the Vanderbilt land stretched as far as the eye could see…all the way into what is now Pisgah National Forest. While the first parcels Vanderbilt purchased had been over-farmed and the forests clearcut and allowed to grow back on their own, the Pisgah Forest tract contained mature stands of trees.

Now, 125,000 acres is a lot of land–almost 200 square miles–and George had no real plans for it. In fact, when Olmsted asked what he planned to do with “all of this land,” George replied that he’d “make a park of it, I suppose.” He knew he wanted an area to hunt and fish, but beyond that…?

Aware that deforestation as a result of over-harvesting and clear-cutting had become a huge threat to American woodlands, Olmsted persuaded Vanderbilt to cultivate and improve the forests that made up the initial purchase and bring them back to health. And he suggested that George manage all of his forest land for game and timber the way gentlemen of wealth did in Europe.

George liked the idea; he already had in mind a working farm using sustainable farming practices, so this was a good fit.

And so, the Work Began

Olmsted trained a crew to begin the work of improving the forests. They removed damaged and poorly formed trees, planted pines, and fixed erosion problems on about 300 acres. He documented this work in “Project of Operations for Improving the Forest of Biltmore,” which was probably the first forest management plan in the U.S.

In it he wrote:

“The management of forests is soon to be a subject of great national, economic importance, and as the undertaking now to be entered upon at Biltmore will be the first of the kind in the country to be carried on methodically, upon an extensive scale, it is even more desirable…that it should, from the first, be directed systematically and with clearly defined purposes, and that instructive records of it should be kept.”

Olmsted said he believed that his proposition that Vanderbilt manage his forests was one of the most important of the suggestions he made in his work at Biltmore.

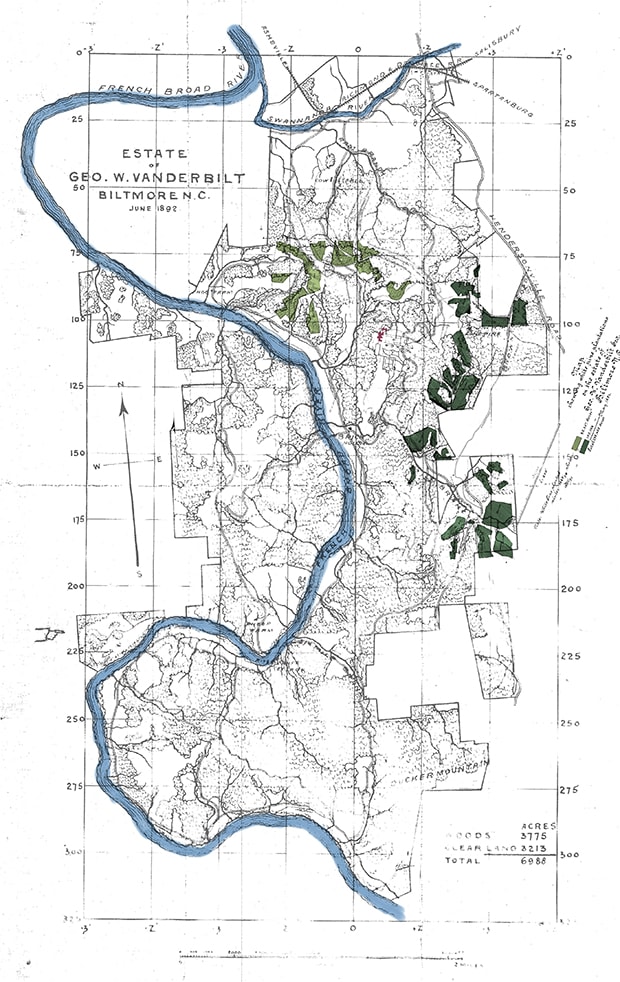

By 1890, the estate had grown to 7,000 acres. At right is a map from the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site showing the areas planted in pines. Light green areas were planted during the winter of ’89-’90. Dark green were planted in the winter of ’90-’91.

The view from the Biltmore Estate today. In the distance is Pisgah National Forest, part of the 125,000 acres George Vanderbilt purchased in the late 1880s.

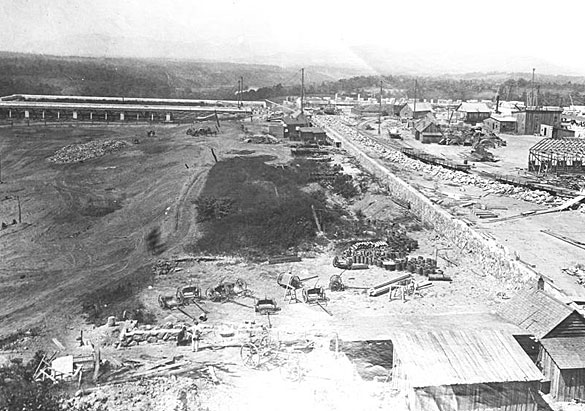

Construction of the Shrub Garden c. 1892. Photo from the Biltmore Collection.

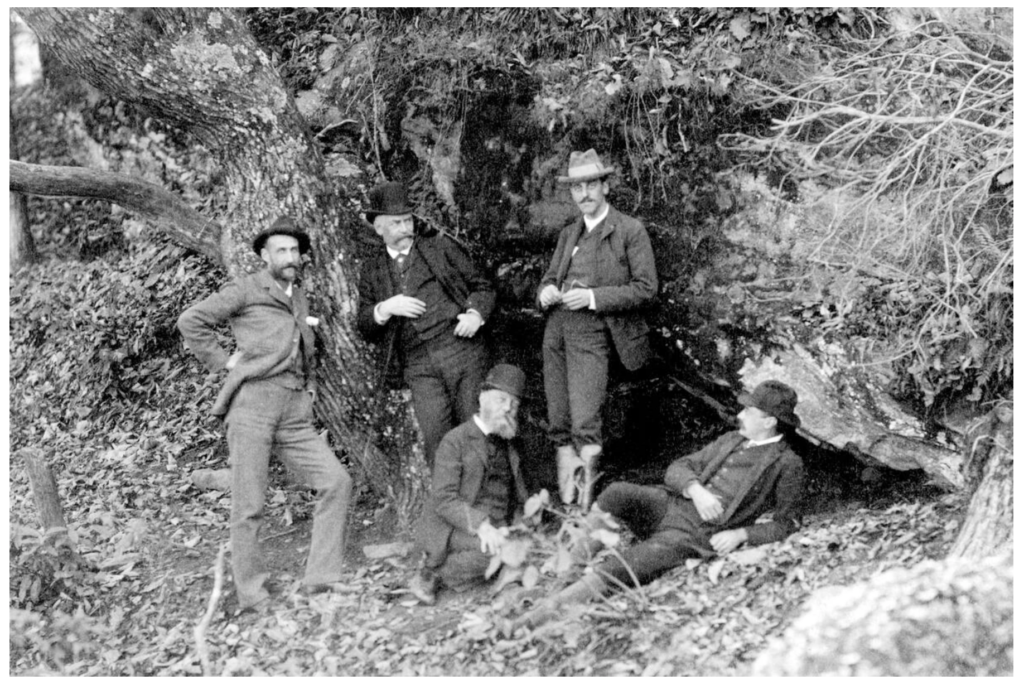

This photo from the Biltmore collection shows (L-R standing) purchasing agent Edward Burnett, architect Phillip Morris Hunt, George Vanderbilt, and seated, Frederick Law Olmsted and his son & landscape architect partner, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.

In 1892, Gifford Pinchot arrived at Biltmore Estate as Biltmore’s first forester.

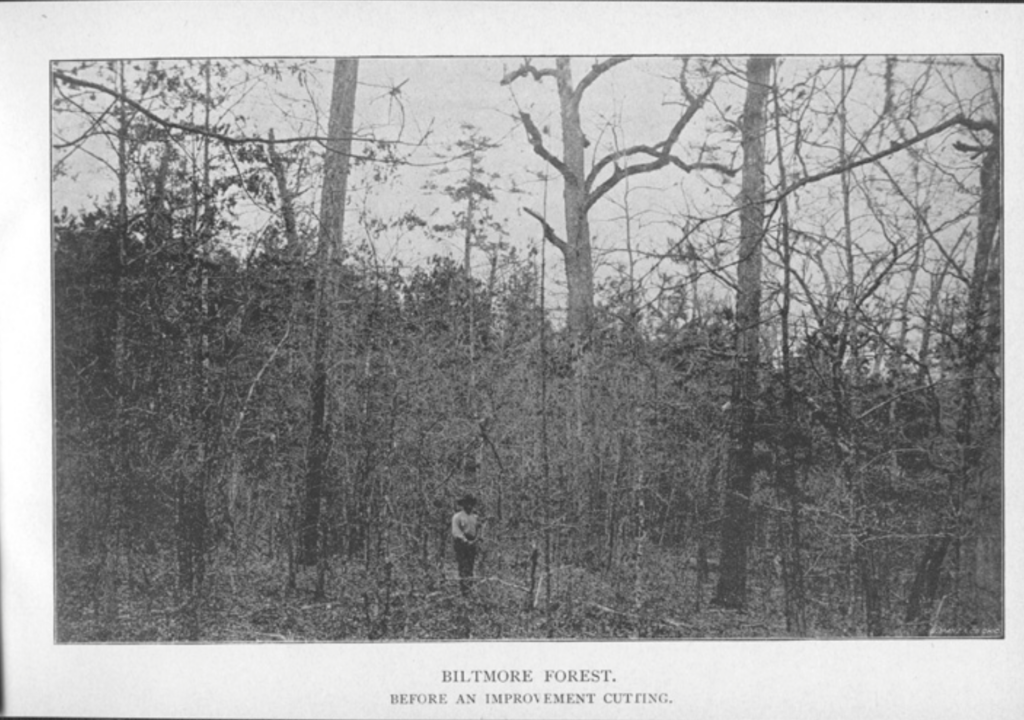

This photo, from Gifford Pinchot’s 1893 publicatioin, Biltmore Forest An Account of its Treatment, and the Results of the First Year’s Work, 1893 shows how Biltmore forest looked before an improvement cut, which involved cutting out misshapen trees and undergrowth to improve the stand of trees.

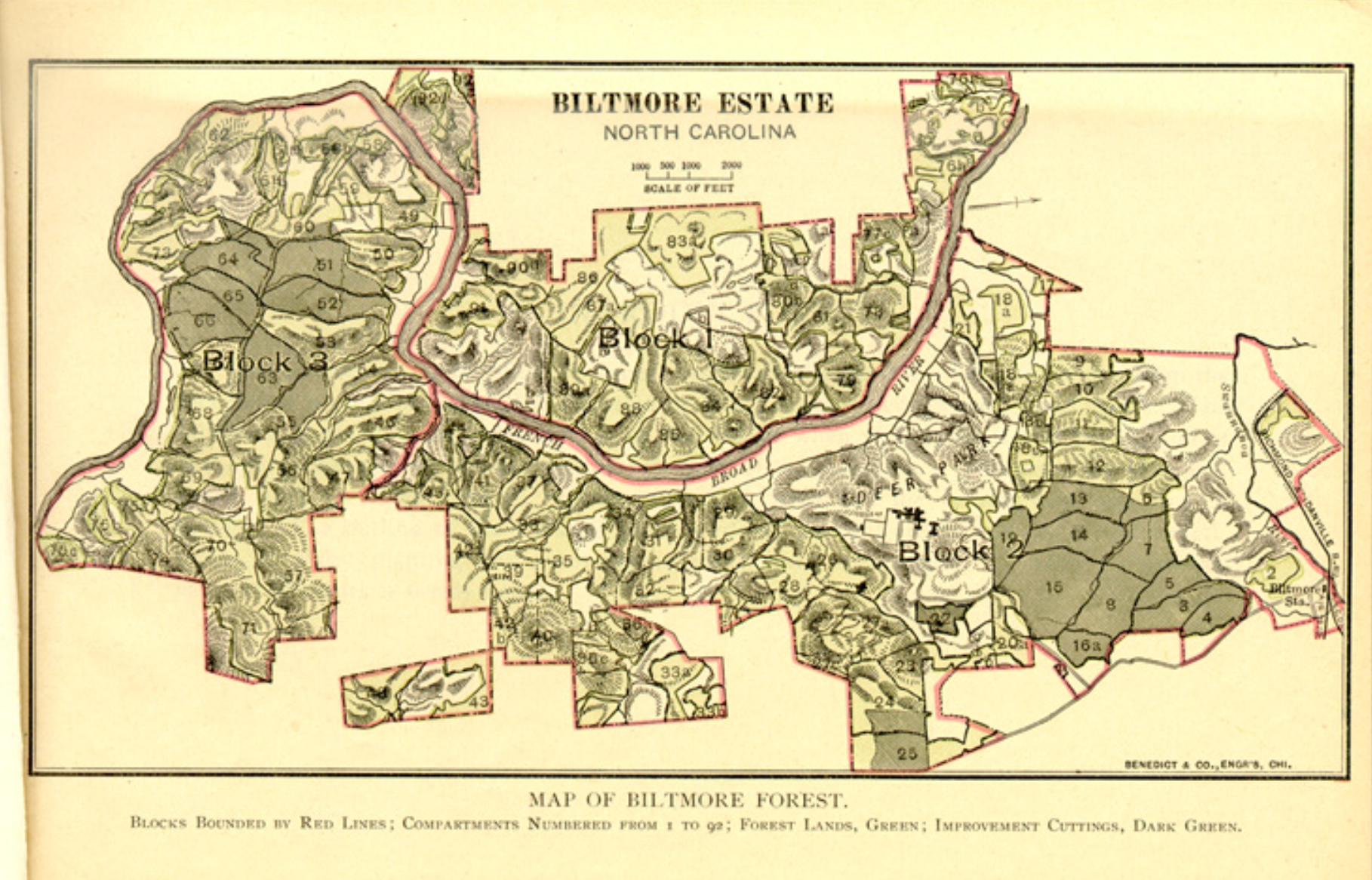

This survey map of Biltmore Forest shows sections or compartments, and is color-coded to show plans for each section. Blocks are bounded by red lines; compartments are numbered 1-92. Forest lands indicated by green; sections marked for improvement cuttings dark green

It appears in Gifford Pinchot’s 1893 report entitled BILTMORE FOREST: THE PROPERTY OF MR. GEORGE W. VANDERBILT: AN ACCOUNT OF ITS TREATMENT, AND THE RESULTS OF THE FIRST YEAR’S WORK. Chicago,, 1893.

Biltmore’s First Foresters

Olmsted was a landscape architect, not a forester. So, in 1892, he encouraged Vanderbilt to enlist the help of an experienced forester. Vanderbilt hired the first forester at Biltmore, Gifford Pinchot, a young man who saw Biltmore Forest as a great way to launch his career. Pinchot had just finished his training as a forester in Europe and at the time, was the only forester in the U.S. Later, as Pinchot began looking around for his next gig, he recommended Dr. Carl Alwin Schenck, a forester from Germany to take over management of the forest project.

As Roxi Thoren wrote in her 2014 article, this moment launched a “model of professional collaboration, as the founding figures of two professions used the design and management of the estate to test the viability of scientific land and resource management.” For a time, she says, “landscape architecture and forestry occupied the same conceptual and physical space.”

Both Vanderbilt and Pinchot believed their mission to be two-fold. First, they were to improve the forests and renew them. Second, they were to introduce forestry practices to show that managing timber stands and cutting timber could be done sustainably and profitably.

Schenck joined the enterprise having no real knowledge of American forests and lumbering. Many years later, he remarked that he had no idea why they had hired him. But his reputation in Europe was excellent. He had a PhD. in forestry, and was passionate about his work.

Schenck and Pinchot learned that forests in the mountains of North Carolina required a different approach to forestry than what they had practiced in Europe.

Harvesting and planting practices common in other areas did not work on the steep slopes of mountains. For example, in their first venture logging in the Pisgah Forest tract, Pinchot insisted that rather than building logging roads to transport timber to the mill, they could float the logs downstream as was commonly done in the northeast. This effort to float timber down the river to Vanderbilt’s mill wound up taking out several bridges and causing property damage to numerous farms. Too, they learned that seeds planted on hillsides that had been cleared of trees were easily washed away by rains or eaten by rodents.

Clearly, they had to develop practices that were sustainable for their environment.

Dr. Carl A. Schenck poses with students of the Biltmore Forest School

Dr. Carl Schenck & The Biltmore Forest School

When Pinchot left the estate in 1895 to pursue other endeavors, (he would eventually become the nation’s first Chief of the U.S. Forest Service), Schenck took over management of the (by then) 100,000-acre forest. Schenck practiced silvaculture, which (according to Wikipedia) is the practice of controlling the growth, composition and structure, of forests, as well as attending to their quality to meet values and needs, specifically, timber production. With a PhD. in forestry from his homeland in Germany, he became known as a person knowledgeable about this new-to-America science. Many young men traveled to Biltmore to learn what they could from him, asking questions and helping to plant trees, cut trees, and improve the forest. Before long, he was running an informal forestry school.

With Vanderbilt’s permission, Schenck founded the Biltmore Forest School using abandoned farm buildings on the estate’s property. This was the first forestry school in the U.S. and trained over 300 students. Western North Carolina is now known as the birthplace of American forestry because of the visionary work of Olmsted, Vanderbilt, Pinchot, and Schenck. Schenck’s students went on to become not only foresters, but teachers and leaders in agriculture and forestry.

Pisgah National Forest & the Cradle of American Forestry

Pisgah National Forest was established in 1914 from close to 87,000 acres of land that Edith Vanderbilt sold to the federal government after George’s death that same year. The taxes on the land were crushing, and they had yet to turn a profit on their forestry work. They couldn’t afford to continue their forestry work and keep up the vast estate. So, following passage of The Weeks Act in 1911, George began pursuing the idea of selling the Pisgah tract to the federal government. He died suddenly in March of 1914; the land sale was finalized in May.

Pisgah National Forest was the first national forest established in the eastern US from private land.

The Cradle of Forestry

In 1968, a 6,500 acre tract of Pisgah National Forest, including the site of Schenck’s Biltmore Forest School was established as The Cradle of American Forestry to commemorate the beginning of forest conservation in the United States. The Cradle of Forestry is run by the US Forest Service and is open seasonally for visitors.

Biltmore Forest School students in front of the schoolhouse

The old archway entrance to Pisgah National Forest as it looked from 1915 to 1936.

The Biltmore Forest School schoolhouse at the Cradle of Forestry

Orchids, forests, landscapes, and the visionaries who designed them…?

No doubt you are wondering how in the world we got here…especially given that when I sat down to write, I was going to write a post about (um maybe) taking care of orchids…or something?

I’m retired, dear readers, and I do what I want. I love garden design, and I love history, and I have a thing for Frederick Law Olmsted. And a thing for forests. So, here we are. I hope you learned a bit. If you made it this far, I imagine you did. (To learn more, see the bibliography with links below.)

I was prompted to write this post by our recent trip to Biltmore to celebrate our anniversary earlier this month. We are season passholders and visit a few times a year, in large part because of our love of the Estate’s gardens, forests, and their history. (Not to mention the great tours, The Bistro, Deerpark brunches, The Inn, the free wine tastings and 20% off everything for passholders.) The Gardens and the Conservatory are my favorite haunts.

While there, I took lots of pictures of orchids and made a video, and I needed a place to put it. (The video, that is.) A post about Olmsted’s Conservatory seemed like a good-enough fit. But then I remembered the trip to Key West and those gardens and down the rabbit hole I went.

So here is the video I made using photos I took in the Orchid Room in the Conservatory. Below that is a video from the Biltmore Estate about the historic gardens. And below that is a long list of references if you’d like to engage in further geekology!

I hope you enjoy!

Orchids at the Biltmore Conservatory

The Historic Biltmore Gardens & Conservatory

References (Go ahead: Geek Out!)

Alexander, W. (Spring/Fall 2011). History On the Road: Asheville, North Carolina, and the Cradle 0f Forestry. Forest History Today. https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2011_History_Road_Asheville.pdf

Angel, H. (January, 2024). Exploring Biltmore’s Historic Orchid Collection. Asheville, NC: Biltmore blog. https://www.biltmore.com/blog/exploring-biltmores-historic-orchid-collection/

Angel, H. (September, 2020). Biltmore: The Birthplace of American Forestry. Asheville, NC: Biltmore Estate History, Biltmore blog. https://www.biltmore.com/blog/biltmore-the-birthplace-of-american-forestry/

Biltmore Estate: Gardens and Grounds page. https://www.biltmore.com/visit/biltmore-estate/gardens-grounds/

Biltmore Estate. The Olmsted Network. https://olmsted.org/sites/biltmore-estate/

Biltmore History: the Biltmore Estate. https://www.biltmore.com/our-story/biltmore-history/

Biltmore: Key Figures. Frederick Law Olmsted. The Biltmore Estate. https://www.biltmore.com/our-story/biltmore-history/key-figures/frederick-law-olmsted/

Biltmore. The Cultural Landscape Foundation. https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/biltmore

Calder, T. (January, 2018). Asheville Archives: Rumors abound in 1889 over George Vanderbilt’s arrival to the mountains. Asheville, NC: Mountain Xpress. https://mountainx.com/news/asheville-archives-rumors-abound-over-george-vanderbilts-arrival-to-the-mountains-1889/

Elliston, J. (March/April 2017). Olmsted’s Great Final Design at Biltmore: How the Famed Landscaper Became Vanderbilt’s Visionary. WNC Magazine. https://wncmagazine.com/feature/olmsted%E2%80%99s_great_final_design_biltmore

Featherman, H. (no date). Biltmore Estate: The Birth of US Forestry, The National Forest Foundation. https://www.nationalforests.org/blog/biltmore-estate-the-birth-of-forestry#:~:text=In%201914%2C%20Edith%20Vanderbilt%20sold,creating%20the%20Pisgah%20National%20Forest.

Forest History Society. Passing the Weeks Act. U.S. Forest Service: https://foresthistory.org/research-explore/us-forest-service-history/policy-and-law/the-weeks-act/passing-weeks-act/

Gardener’s Supply Company. How to Grow Orchids: A comprehensive guide to orchid care. https://www.gardeners.com/how-to/growing-orchids/5072.html#orchidcare

Kiely, A. (June, 2022). Biltmore Estate: Frederick Law Olmsted’s Final Masterpiece. The Collector. https://www.thecollector.com/the-biltmore-estate-frederick-olmsted-masterpiece/

Klein, J. (August, 2018). Heritage Moments: Frederick Law Olmsted and the stroll that saved Niagara. Buffalo-Toronto Public Radio, WBFO, NPR. https://www.wbfo.org/heritage-moments/2018-08-13/heritage-moments-frederick-law-olmsted-and-the-stroll-that-saved-niagara

March, J. (May, 2023). Biltmore Estate. The Construction of the Biltmore House. Asheville, NC: Biltmore Estate History, Biltmore blog. https://www.biltmore.com/blog/the-construction-of-biltmore-house/

National Forest Service. Cradle of Forestry. https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/nfsnc/recarea/?recid=48230

Neveln, V. (September, 2023). The Best Orchid Care to Keep These Beautiful Plants Thriving. Better Homes and Gardens. https://www.bhg.com/gardening/houseplants/care/how-to-care-for-orchids/

New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Olmsted–Designed New York City Parks. New York: https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/olmsted-parks

Pinchot, G. (1893). Biltmore Forest An Account of its Treatment, and the Results of the First Year’s Work, 1893. North Carolina State University Special Collections. https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/specialcollections/forestry/schenck/series_v/gfi/PinBilt.html

Sexton, A. (March 2023). Biltmore: Olmsted’s Living Masterpiece of Landscape Design. Asheville, NC: Biltmore Estate History, Biltmore blog. https://www.biltmore.com/blog/biltmore-olmsteds-living-masterpiece-of-landscape-design/

Slusser, D. W. (no date). Raoulwood and the Origins of Biltmore Forest. Preservation Society of Asheville, Buncombe County. https://psabc.org/raoulwood-and-the-origins-of-biltmore-forest/

The Blue Ridge Heritage Trail. Cradle of Forestry, the Blue Ridge Parkway. https://blueridgeheritagetrail.com/explore-a-trail-of-heritage-treasures/cradle-of-forestry/

The Gardens Hotel Property Map. Key West, FL: https://www.gardenshotel.com/property-map

The Gardens Hotel, Key West. Key West, FL: https://www.gardenshotel.com/

The Gardens Hotel. Our Hotel’s History: Turning a Dream into Reality. Key West, FL: https://www.gardenshotel.com/history

Thoren, R. (Spring, 2014). Deep Roots: Foundations Of Forestry In American Landscape Architecture. Scenario Journal, 04: Building the Urban Forest. https://scenariojournal.com/article/deep-roots/

Video: America’s First Forest. https://www.tpt.org/americas-first-forest-carl-schenck-and-the-asheville-experiment/video/americas-first-forest-mRjqBU/

Welton, M. (June 2010). Near Asheville, N.C., a Triple Threat at Biltmore Estate. Architects & Artisans: Thoughtful Design for a Sustainable World. https://architectsandartisans.com/blog/a-triple-threat-at-biltmore-estate/

Wikipedia. Jackson Park (Chicago). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jackson_Park_(Chicago)

Wikipedia. The Biltmore Forest School. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biltmore_Forest_School

Thank you for putting all of this together. I loved reading about the development of Biltmore and seeing the old pictures. Amazing! The videos of the flowers and the grounds have me convinced to make a trip this spring to see them all again. It has been many years since I visited. It was also so interesting learning about the other projects of Olmsted, especially Niagara Falls. I am so glad you included all the additional links at the end. I am looking forward to exploring them.